Déborah Heintze, M. Sc., is co-founder of Lunaphore. A mathematics fan from a very young age, Déborah chose to add a little more life into her research – so she embraced life sciences. If engineering has its own appeal, what about life engineering!

Her motto: hard work and trust in the team is essential to go far.

Her Swiss firm Lunaphore is born with the vision of bringing – omics like approaches to in-situ tissue analytics for cancer research and diagnostic purposes. Lunaphore develops innovative tissue staining platforms based on a cutting-edge technology, providing high quality results much faster than current techniques and aiming to automate some of the most sophisticated assays thanks to high-precision fluidics. Lunaphore further enables digital pathology through the integration of imaging systems such as a microscope with sequential data extraction. Lunaphore has been repeatedly recognized for its innovation. To date, Lunaphore completed several financing rounds with the latest one at 25 million to advance its solutions to support cancer research.

We met a super nice, modest and remarkable leader. Please get into her story and share it around!

Can you describe your path to becoming a scientist? What and / or who helped you in your professional choices?

As far as I can remember, I loved two disciplines: sports and mathematics. I was particularly talented in mathematics. When I was young, I participated in several local and international competitions in mathematics. They consisted in logical problems* – for me, this was fun, which shows how much I really like mathematics! At a very young age I made it to the second place at the international final in Paris. It was my mathematics teacher at the time – a true fan as well – who was registering me in these competitions. It was a nice encouragement.

In my mind, it was always quite clear that I was going to work either in science or in sports. A combination of both would have been nice. However, at some point – for me, when I joined the University – one has to choose one way or the other. I had studied mathematics and physics in High School. I found out at that time the Life Sciences Faculty of EPFL (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne).

The life science bachelor at EPFL is a mix of different fields, including mathematics and others like biology and chemistry. Even if I did not really know what to expect with these, they seemed fun, so I chose that option! [Laughs]

My father did physics at EPFL. It certainly influenced my choices a bit. It helped me projecting myself in the scientific field. Moreover, my mother was a nurse – a different domain but still in the medical field. Both have obviously played a role in my path – I did not engage in a world completely different from theirs. Further on, I took care of myself, trying to get the good grades to move forward. Well, that is where I come from.

[ *editor’s note: Have a look at Fédération Française des jeux Mathématiques ]

How does your research field contribute to society?

Be a scientist! It was my motto at first. But I wanted to have an impact on the biomedical side of it. I was mentioning sports before but, in the end, I chose human medical science in general. The subject of my master’s thesis was the reconstruction of cardiac tissues – for example instead of transplanting a heart, you can think of reconstructing part of the deficient tissue.

With Lunaphore, we are contributing to the cancer research field. I really like that. At least you can feel that you are developing solutions that have an impact.

Should I have to rethink this choice, I would either do what I do or contribute to issues related to the environment. Also, I would be interested in disciplines that have a shorter-term impact than what I am doing now. Our company is supporting cancer research. We cannot see the direct impact of research on a daily basis. Yet, our work will ultimately lead to concrete applications within the diagnostics field. I am very fond of what we are doing now with Lunaphore.

How do you convince investors?

We ran four rounds of investments. To convince, you need a combination of many different elements, including credibility and visibility. You need to be visible in the media as well as on other channels.

Yet, ultimately, I believe that most investors invest in a team. They want to see a great combination of individuals and talents.

Not the common three male PhDs with the same kind of profile combination.

Investors want diversity. It could be gender diversity or diversity in ways of thinking for instance. Team members have to trust each other, to share the same values, to be able to come up with new ideas. The team is very important. From Day 1 to the moment they decide to make an investment, investors want to see a movie, not just a picture at some point in time. At Lunaphore, our movie showed them how we are able to deliver and helped them trust us. We have always set up ambitious goals and showed that we can achieve them. It is a matter of trust and creating a strong relationship with investors. Today they trust us a lot, and listen to us when we propose changes, even important changes in strategy. They are supporting us in taking the right decisions.

One important aspect is to keep them informed. We regularly send them newsletters or reports so they can see we are moving on. Our initial lead investors were local – mostly private Swiss German investors. In the last financing round, a large private equity fund invested in Lunaphore through its Japanese-owned company. It is our first lead investor based outside of Switzerland.

What, in your view, is the role of public relations in supporting science and how do you use them in your own strategy?

We have always targeted a worldwide audience even though some newsletters are more for specific customer segments. But in general, we are targeting widely. Should we choose some Newswire, we specify US, Europe. Having said that, the ecosystem of startups in Swizerland is very strong, and where the news resonate most, especially at the early stage phase of the company, where a lot of buzz is created around new startups thanks to local competitions or other types of achievements. At the end, you get very well known in the Swiss environment. Yet, if you go everywhere else, only a limited amount of people would know about Lunaphore. Except for investors, partners and customers, we do not necessarily need such high visibility outside of Switzerland. This very first network in Switzerland is really important when you start a company, but you then need to scale it up.

“Product through the network” mindset leads you to investors.

In your view, how is PR important for science?

I see quite a bit of science in the media. Yet, sometimes, it is misleading. I know vulgarization is important for the general public to understand science. Also, visibility is needed so that people know everything that is ongoing. However, if science is made to simplistic, it might get people to think that what we are doing is easy to do and place the expectations too high. As if we – at Lunaphore – should commit to solve every issue in cancer while we are only a link in the very big chain of cancer research.

I would be happy if there were a bit more media on science, simplified but not misleading.

Do you observe major differences on how science is supported in Switzerland or in the US?

I lived in the US for a year. I did my master’s thesis in Boston, a program between Harvard University and MIT – the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I was doing research on cardiac tissue. I did not have PR experience when I was there. I spent 16 hours a day in the lab to get the research moving – while still having an intense party life during weekends [laughs]. One thing surprised me there: when I thought of Harvard and MIT, I imagined fantastic labs, a big quantity of top-class material, etc. However, I realized that at EPFL you have equally good – if not better – support and infrastructure than on the other side of the ocean. Anecdote: there were two microscopes in my facility and I had to book one at 4 A.M to get a free slot, so I was coming at the lab during the night. Furthermore, the environment in the US is particularly competitive. Goal: you want to make sure you’re the first to publish.

This – the mindset of publishing for publishing – made me go away from research at some point. I wanted to do something much more applied and this is also why I chose not to get a PhD.

So I did my Master and my research in the US, looked for a job for a few months and then decided to jump on the Lunaphore adventure.

Should you encourage young girls to get into science, what would you say?

Not to be shy.

Girls should consider they are capable of doing what they want. Still we do not see enough role models. Women tend to need the support of other people to build self-confidence.

If someone else can do something, well, women can do that too. Girls should not be scared. At the Life Sciences Faculty at EPFL, we were half women half men. Guess what, these studies are not easier than studies in other faculties. The levels of mathematics, physics or chemistry is even higher than in some other EPFL faculties. Yet, from the outside, life sciences might look easier, though, maybe because it includes biology? Girls should be able to see that there is as much fun in the other fields, too. What if each faculty was named “life” something and not “engineering” something [laughs]. This word [engineering] is not that attractive to girls, is it? Although, once you have the “engineering” title you feel very proud.

Is there something you would do differently or advise young scientists to avoid doing?

I would not change what I did so far. However, I started a marathon like a sprint.

When you are working so much, you consume a lot of energy. You think that this is going to be just for a few years but actually you see that it is prolonging a few more years. Advice: you should start a marathon fast but not like a sprint. Now I think I have a good work-life balance – kind of – compared to the beginning where I worked from 6 a.m. to midnight and over the weekend! This isn’t sustainable. One should keep a good work-life balance from the beginning.

An anecdote to share with us about your journey as a woman, a woman in science, a leader?

You know those situations where you are the only woman in the room, alone with many men, negotiating an important matter? Even if I got used to that – I was evolving only with men and one other woman in High School – it makes a difference. I realized that I might not be as comfortable as if there were other women in the room.

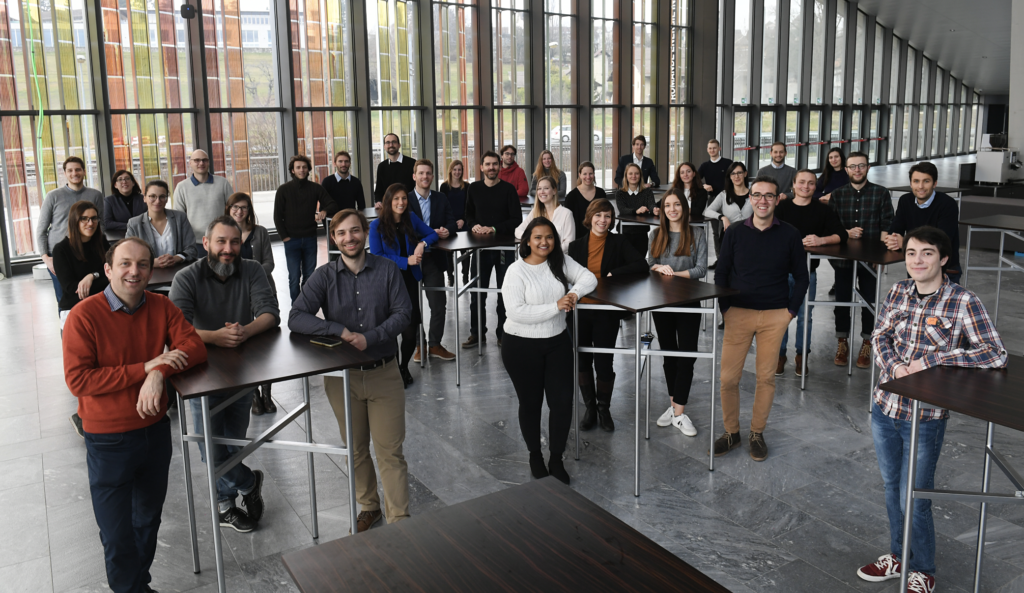

Interestingly, sometimes I was with a lot more women in the room and only one of my male colleagues. He was not so comfortable because he thoughts one of those women was frightening. Seems that the other way around also makes a big difference. The number of women around the table has an influence on my level of confidence or the way I would express myself. At Lunaphore, we are around 50 people and we are more or less half women half men.

This has been the case throughout our history and growth, even if we did not set up quotas. By chance, we managed diversity. Diversity in gender, but as well in nationalities and mindset.